De verticale lijn is de lijn van het leven! De horizontale lijn is de lijn van de dood

Dit is de indoctrinatie die Dan Van Severen (1927-2009) in Sint-Lucas zijn studenten ingepeperd heeft. Eén van hen, André Van Schuylenbergh, citeert deze doctrine nog geregeld met de nasale intonatienabootsing van de meester. 'Doctrine' is het juiste woord voor het pedagogische principe van het Sint-Lucas van toen. Enerzijds, de brave duivenmelkersstijl van de animist, Gaspard De Vuyst (1923-2020), anderzijds de mystieke abstractie van Dan Van Severen, als twee alternatieven. De eerste leerde hoc klassiek te schilderen, de tweede zette aan tot nadenken of volgzaam gehoorzamen.

Dan Van Severen is een belangrijk Belgische kunstenaar, tijdgenoot van Jan Burssens (1925-2002) die via het abstract expressionisme de rechtstreekse bevrijding aanmoedigde in de Gentse academie en van Octave Landuyt (0 1922), die schildertechniek bijbracht, samen met de inzichten in het surreële aan de Gentse regentaatschool. Bij Van Severen gebeurde de bevrijding onrechtstreeks, bij dezen die zich niet lieten onderwerpen aan regeltjes en aan een specifieke esthetische ideologie. Misschien is de negatieve bevrijding efficiënter dan de positieve. Zich afzetten tegen doctrines kan betere resultaten geven, dan de illusie uit het niets te kunnen creëren, met als basis een overdreven geloof in het Zelf en de vrije creatie. Jezuïeten kunnen goede atheïsten worden, om even de esthetische bevrijding te vergelijken met de ethische.

André Van Schuylenbergh is zo een ongehoorzame, zonder respectloos te zijn, ten aanzien van zijn leermeester. Hij had snel door dat zijn optimistische levensvrolijke persoonlijkheid niet compatibel was met ihet sombere, pseudo-mystieke, christelijk metafysisch temperament van Van Severen. Wat niet wegneemt dat de meester wist wat het plastische vermogen van een lijn inhoudt, wat een aantal lijnen samen als interess.ante

vorm kunnen betekenen en wal kleurtinten als werking kunnen veroorzaken: basisvormen, boeiende harmonieën, essentiële verhoudingen, zekerheden die opduiken wanneer men meent de eenheid tussen de dingen beet te hebben.

Van Schuylenbergh was niet zo opgezet met zo een spirituele kijk op het leven. Om het met een religieuu metafoor te zeggen, hij wierp zijn kap- over de haag van het Sint-Lucas-systeem en smulde lustig van de appelboom en zijn paradijselijke mogelijkheden van het picturale: de kleur als feestelijk decorum voor de ceremoniemeester van het levensblije kijken naar de dingen. Thema na thema verbloemt André aspecten van de wereld.

Zijn magnolia's natuurlijk, maar het is meer dan dat. De typische lineaire Van Schuylenbergh schicht geeft een essentie van de vrouwelijkheid weer.

Geen ontologische diepzinnigheid waarin het wezen uit de onverborgenheid treedt à la Heidegger. Gewoon een virtuoze krabbel waarin de vrouwelijke frivoliteit haar ongrijpbaarheid verbergend toont à la Nietzsche. Nietzsche begint zijn Jenseitsvon Gut und Böse met "Verondersteld dat de waarheid een vrouw is?" De waarheid is een vrouw maar ze is dat niet zoals de filosoof, de man, haar graag heeft, nl. als identificeerbaar, grijpbaar, eenduidig en toegankelijk, zo is de interpretatie die Jacques Derrida aan deze gedachte geeft. Haar erotische soevereiniteit doet zich aan de man als een voortdurende wispelturigheid voor. De waarheid, als vrouw, lijkt zich aan elke filosoof, als man over te geven. Maar dit is maar spel. De Vrouw/Waarheid weet dat er geen diepste diepte is en dat aan het afdalen geen einde komt. Dit haJlucinerende sluierspel verlaat de oppervlakte eigenlijk nooit. "Want als de vrouw waarheid is, weet zij dat er geen waarheid is en dat men de waarheid niet bezit'; schrijft Derrida. (J. Derrida, tperons. Les styles de Nietzsche, Flammarion, Paris, 1978).

Het was de popart die André Van Schuylenbergh op weg naar zichzelf zette. De popart reageerde met een oproep om terug met de voeten op de grond te komen, nadat het abstract expressionisme zichzelf wat opgehemeld had met metafysische dimensies. Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) bracht de chaos niet, maar zou een verborgen orde vertonen, zoals Anton Ehrenzweig (1908-1966) stelde. Mark Rothko (1903-1970) zou geen gezellige ingekleurde ruimtes creëren, maar zijn doeken zouden fungeren als bezinningsmedium voor contemplaties van alle soort. De 'zips; de verticale lijnen in egale kJeurvlakken, van Barnett Newman (1905-1970) is geen visueel kleurspel, maar abstracte interpretaties van de Joodse theologie.

Dan Van Severenwas geen abstract expressionist, om de eenvoudige reden dat hij allesbehalve een expressionist was en geen lyricus, maar een mysticus. Toch is er

een verwantschap in de wending die André Van Schuylenbergh nam tegenover dit soort meditatieve kunst en de popart die tegen het abstract expressionisme reageerde. De religie is de moeder van de kunst en deze geraakt zelden haar oorsprong kwijt via haar steeds maar vrij snel optredend moraliserend of sacraliserend vermogen. De popart betekent een secularisering van de wereld. Kijk eens naar de wereld, zoals deze er vandaag uitziet en mystificeer niet, is de boodschap. Een spiegelei is een spiegelei. Coca-cola is coca-cola. Een soepblik is een blik soep. Waspoeder is waspoeder. De auto-crashes zijn de drama's van vandaag. Van de problemen zoals uitgebeeld in het antiek theater, ligt de popartiest niet wakker. De elektrische stoel is een actueel apparaat van bestraffing, niet

het kruis. De filmsterren en zangidolen worden aanbeden, niet de heiligen. Het stripverhaaJ heeft de plaats van de boeken vol lettertekens verdrongen als snelle communicatie. Aan eettafels in restaurants beleven we de sociale communie, niet geheiligd in kerken op bidstoelen op de knieën.

Popart is werelds.

Men kan nooit genoeg benadrukken hoe zeer de popart een teken aan de wand geweest is als doorbraak van de moderniteit en de breuk met de

traditionele maatschappij 'van voor de oorlog', zoals men dat tijdperk pleegt aftesluiten. Hoofdkenmerk daarvan in het alledaagse leven is de overname van het handgemaakte door de fabricage-massaproducties. Een vuilnisblik met borstel werd vervangen door een stofzuiger. Een bellenman verloor zijn functie door radio en tv. Affiches zijn geen steendrukken meer, maar rollen van de pers. Geef ons heden iedereen zijn gazette bij het dagelijks brood.

Kevers, Deux-chevauxs en de Fiat 500 zorgden voor de democratisering van het autoverkeer. Meubilair werd fabriek gemaakte design. Maatkledij, gesneden, genaaid en gestikt door kleermakers in ateliers van grote kledingzaken wordt vervangen door confectie in boetieks. De kJeren maken de man niet meer, de man kiest zijn kleding. Ze fungeren overigens niet meer als teken van de sociale klasse waartoe men behoort, want de idee van democratisering, basisprincipe van de moderniteit, verbiedt het tonen van

de verschillen. Hoewel dat verbod zijn weelderige omzeilingen kent, leidt het tot een semiotische chaos, die later de mooie naam 'multicultureel' meekreeg. De werkmansbroek werd een jeans die in zijn postmoderne versie nog een machinaal aangebrachte scheur boven de knie meekrijgt. Kleding bevestigt de verscheidenheid, of noem het 'individualisme: op welke wijze men dat ook waardeert. Want het moet gezegd, sommige werken van de popart worden wel eens 'neo-dadaïstisch' genoemd en het postmodernisme 'neopop'. Er zit in de popart ook een uiting van kritiek op de massacultuur. Ironie en satire zijn niet veraf. Geen enkel fundament kan fundamentalisme funderen.

De wieg van de popart stond in Londen in het jaar 1952, inderdaad: het geboortejaar van André Van Schuylenbergh. In de schoot van het ICA kwam de'Independent Group' voort. Het ICA, het 'Institute of Contemporary Arts' in hartje Londen, werd in 1946 gesticht in de geest van de onverdroten naoorlogse behoefte aan vrijheid. Het wou ruimte geven aan kunstenaars, auteurs en wetenschappers om van gedachten te wisselen opeen andere manier dan dat in de traditionalistische Royal Academy gebeurde.

Multidisciplinaire experimenten en de nadruk op de sociale dimensie van kunst, werden aangemoedigd. Daar groeidein de jaren '50 'The Independent Group', die het opnam tegen het te heersende modernisme, dat een vrij elitair systeem geworden was. Ze onderzochten het belang van de populaire cultuur binnen de consumptiemaatschappij. Aan één van hen, Lawrence Alloway (1926-1990), een bekend geworden criticus, schrijftmen het in voege brengen van de term 'popart' toe.

Niet iedereen werkte zoals Andy Warhol (1928-1987), de Amerikaanse 'pope' van de popart, multimediaal rond de hogerop aangegeven thema's, die ik zonder aan hem te refereren aanhaalde. Sommigen bleven echter de schilderkunst trouw. Zo bijvoorbeeld David Hockney(01937), die een ruimtelijke wereld creëerde, vol nieuwe kJeuren die de lichtheid van het bestaan suggereren, onafgezien de draaglijkheid ervan.

Door deze heldere veelklJeurigheid en speciale vorm van spatiale setting wordt André Van Schuylenbergh aangetrokken. Hij maakt er zijn eigen wereld van, met meer dan één knipoog naar David Hockney, de uitvinder van dit soort romantische popart. Het betreft een moderne romantiek, zonder verheerlijking van het verleden als een teloorgegane betere wereld. Een die gebaseerd is op de celebratie van het dagelijkse leven en de schoonheid van de dingen.

'This is tomorrow' was de titel van één van de eerste popart-tentoonstellingen in de Whitechapel Art Gallery te Londen (1956). De naoorlogse verwachtingen voor een nieuwe gelukzalige wereld waren hoog. Vrolijke kleuren en vredige ruimten moesten dit beklemtonen. Het epicuristische 'pluk de dag' was de onderliggende boodschap. Deze tentoonstelling kenmerkte de wending die de kunst aan het nemen was in het Londen van die tijd. Men vindt die geest ook bij Hockney. Zijn figuren vertoeven aan zwembaden of zitten gezapig onderuitgezakt in een stoel zichzelf te zijn, dagdromend over het mooie leven.

André Van Schuylenbergh steekt de inspiratie die hij verkreeg van zijn vijftien jaar oudere collega ook niet onder stoelen of banken. Een mooi aantal hommage portretten die hij van David Hockney maakte, liegen er niet om. Klap op de vuurpijl van deze waardering is zijn aankoop met zijn spaarcenten van een steendruk in 1978 van Hockney voor 40000 Belgische frank (1000 euro) bij Marc Deweer te Otegem.

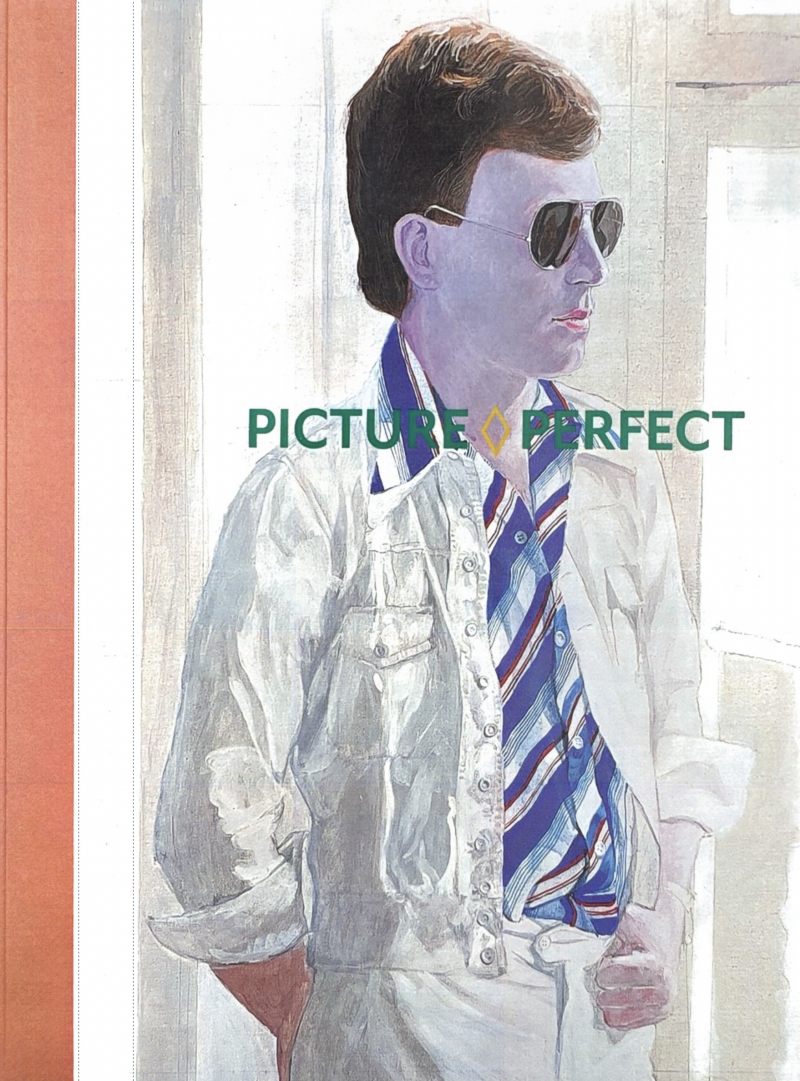

De wijze waarop hij op die nieuwe picturale taal inspeelde, kreeg van sommige critici en galeristen aandacht, maar André maakte er geen gebruik van. Die waardering was ook begrijpelijk, want Van Schuylenbergh vond er onmiddellijk zijn eigen weg in. Deze popart-werken worden bijna vijftig jaar later voor het eerst vertoond in de tentoonstellingsruimte DISKUS(Aalst, december 2022). Keurig uitgedost in de anticonforme jaren '70 kledij poseren zijn familieleden, vrienden en gewaardeerde collegae in een vrolijk decor. Het zelfportret mocht uiteraard niet ontbreken. De blijheid voor het leven staat in schril contrast met het existentieel miserabilisme dat aan de filosofie van Sartre vastzit. De wereld kan ook mooi zijn, toont André Van Schuylenbergh, de schilder van het optimisme, ons. Gelijk heeft hij, al was het maar enkel met carnaval.

The vertical line is the line of life! The horizontal line is the line of death.

"The vertical line is the line of life! The horizontal line is the line of death" was the dogma Dan VanSeveren (1927-2009) instilled in hisstudents at Sint-Lucas. One of those, André Van Schuylenbergh, still regularlycites it, unfailingly delivering hisimpression with the master's nasal intonation. 'Dogma' is the right word for the pedagogical principle that was honoured at Sint-Lucas at the time.On the one hand the inoffensive pigeon fanciers' style of the animist Gaspard De Vuyst (1923-2020), on theother hand Dan Van Severen's mysticalabstraction: these were thealternatives. The former taught his students to paint in the traditional style, the Jatter incited them to either reflect or obey him unwaveringly. Dan Van Severen isa major Belgian artist,a contemporary of Jan Burssens (1925-2002), who openly encouraged the Hberation via abstract expressionism at the Ghent academy and Octave Landuyt (01922), who taught painting techniques while also introducing insights into surreaHsm at the art education department of the Rijksnormaalschool in Ghent. Under Van Severen's tutelage, the Hberation happened more indirectly, at least for those pupils who refused to submit to rules and regulations or toaspecific aesthetic ideology. Maybe his negative liberation was more effective than positive liberation? Rebelling against doctrines may yield better results than fostering the illusion that it is possible to create from scratch, based on exaggerated faith in oneself and in free creation. Jesuits may become good atheists, toestablish an analogy with ethica!liberation. André Van Schuylenbergh was such an insubordinate, though he was never disrespectful to his teacher. He soon figured out that his optimistic,life-affirming, cheerful personality was not compatible with VanSeveren's sombre, pseudo-mystica!, Christian metaphysical temperament. Which is not tosay that the master didn't know the plastic potential of a line, the interesting shapes that can emerge out of acouple oflines, or what effect colour shades may have: basicshapes, interesting harmonies, essential proportions, the sense of security derived from the illusion of having grasped the oneness of things.

Van Schuylenbergh was not that keen on aspiritual outlook on life. Like a monk abandoning his monastery and rejoining the world, he gave upon the Sint-Lucas-system and lustilyenjoyed the fruits of the apple tree and its paradisiacal pictorial opportunities:colour as the festive decorum for the master of ceremonies of the resolutely joyful outlook on life. In his treatment of one theme after another, André turnsvarious aspects of the world into their floweryversions. As with his magnolias, obviously, but there is more.

The typical linear Van Schuylenbergh-bolt represents an essence of femininity. There's no appetite here for any ontological profundity, with the essence emerging from unconcealedness, à la Heidegger. Just a virtuoso scribble, sketching feminine frivolity as il hides its elusiveness, à la Nietzsche. Nietzschestarts his Jenseitsvon Gut und Bösewith the question: "What if the truth isa woman?" The truth is a woman, bul not in the way the philosopher, a man, would like her to be: identifiable, tangible, unequivocal, accessible- as Jacques Derrida interpreted this thesis. To a man, her erotic sovereignty seemslike incessant capriciousness. It seems as if the truth, a woman, will surrender toevery philosopher, a man. But this is just play-acting. The Woman/Truth knows there is no depth of depths and that there is no end to thedescent. Tuis hallucinogenic veil dance is never anything but superficial. "For ifwoman is truth, she knows there is no truth and that truth has no owner."(J. Derrida, fperons. Les styles de Nietzsche, Flammarion, Paris, 1978).

Pop art was the movement that pointed Van Schuylenbergh the way to himself. When abstract expressionismstarted to glorify itself byattributing all kinds of metaphysical dimensions to its creations, pop art reacted with a plea to please keep their feet on the ground. According to Anton Ehrenzweig (1908-1966), Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) had not brought chaos to the art of painting, but a hidden order. Mark Rothko (1903-1970) had not created pleasantly colouredspaces, but canvases that served as mediums for all kinds of contemplation.The 'zips' painted by Barnett Newman (1905-1970), vertical linesseparating colour fields, were not just elements in a play of colours, but abstract interpretations of the Jewish theology...

Dan Van Severen was not an abstract expressionist, for the simple reason that he wasanything but an expressionist-and certainly no lyrica! one, as he wasa mystic. And yet there is a kinship in André Van Schuylenbergh's response to this type of meditative art and the way pop art reacted to abstract expressionism. Religion is the mother of art, and the fact that art rarely manages toshed itsorigins is due to her moralising or sacralising powers.

Pop art isallabout the secularisation of the world. See the world as it looks today and don't mystify, is its motto. A fried egg is a fried egg. Coca-cola is coca-cola. Asoup can is a soup can. Washing powder is washing powder. Car crashes are dramas happening today. Problems as represented in ancient Greek theatres are ofno concern to the pop artist. The electric chair is a device for punishment currently in use; the cross is not. Movie stars and football idols are adored, not saints. Comicstrips have replaced hooks exclusively filled with characters as accessible means of communication.

Social communion iscelebrated sitting around restaurant tables, not hallowed in churches kneelingon prayer benches. Pop art is of this world.

It is hard to overstate the role of pop art as a sign on the wall signalling the breakthrough of modernity and the rupture with traditional 'pre-war society', as thisera is usually defined. lts main characteristic in daily life is a transition from hand-madeobjects to mass-produced goods. The dustpan and broom were replaced with a vacuum cleaner.The town cryer was replaced by radio and tv.

Posters are no longer lithographs, bul roll off presses. Give us each day our individual newspaper with our daily bread. Beetles, 2CVsand Fiat 500s democratised car traffic. Furniture was henceforth mass-produced design. Bespoke clothing, cut, fitted and stitched by tailors in the workshops of large dothing stores, was replaced byconfection sold at boutiques. Clothes no longer defined the man; he chose whatever he wanted to wear. Clothing no longer functions asa sign of the social class we belong to, as the idea of democratisation, the fundamental notion of modernity, prohibits the emphasising of differences. Though this ban has been known to be blatantly bypassed and frequently stillis, it has led toa semioticchaos that was later on euphemistically named 'multicultural: The worker's heavy-duty work trousers became jeans, which, in its postmodern version, has had a mechanically applied tear added just above the knee.

For it must be said:some pop art works have been designated as 'neo-dadaïst: and postmodernism'neo-pop'.Pop art also features some criticism of mass culture. Irony and satire are never far off. No fundament can underpin fundamentalism.

Pop art popped up in London in the year 1952, which, indeed happens to be André Van Schuylenbergh's year ofbirth. That was when, within the ICA, an 'Independent Group' saw the light of day. The ICA, the 'Institute of Contemporary Arts' situated in centra!London, had been founded in 1946 in a spirit of post-war freedom-seek.ing. It aimed to provide a platform to artists, authors and scientists to exchange views in a way that was radically different from the traditional ways of the Royal Academy. Multidisciplinary experimentsand a focuson the social dimension to art we reencouraged. From within this Institute, in the 1950s, 'The Independent Group' stood up against modernism, which had by then become the rather elitist dominant system. The Group studied the significance of popular culture in consumer society. To one oft hem, Lawrence Alloway (1926-1990), who became a well-known critic, has been ascribed the mintingof the term 'pop art'.

Andy Warhol, the American 'pope' of pop art (1928-1987) operated as a multimedia artist on the subjects (soup cans, car crashes...). I mentioned earlier with a nod and a wink to his oeuvre.

But that was not how all pop artists operated. Some of them remained faithful to painting. As did, for instance, David Hockney(01937), whocreated a spatial world full of new colours that suggest a lightness of being, irrespective of its bearability.

Attracted by its multicoloured brightnessand unusual form of spatial setting, André Van Schuylenbergh created hisown version of pop art, with more than a nod to David Hockney, the inventor of this type of romantic pop art.

But theirs is a modern romanticism, without anyglorification of the past as a better world regrettablygone by. Their world was based on a celebration of daily lifeand the beautyin objects. 'Tuis is tomorrow' was the title of one of the first pop art exhibitionsat the Whitechapel Art Gallery in London (1956). Post-war expectations of a blissful new world were high. Cheerful colours and peaceable spaces were meant to emphasise this mood. An epicurean incitement to 'seize the day' was the underlying message.Tuis exhibition was characteristic of the turn art was taking in the London of that era.The same spirit emanates from Hockney's works.The figures in his paintings are lounging near swimming pools or sitting around relaxedJy, slumped in their seats, daydreaming of the beautiful life.

André Van Schuylenbergh makes no secret of the inspiration he took from this colleague, who is his senior by fifteen years. The respectable number of portraits in homage he painted of David Hockney speak for themselves. The cherry on the pie ofhis appreciation must be the fact that in 1978 he acquired a lithograph by Hockney for 40000 BEF (1000 €), the total amount ofhis savings, at Marc Deweer Gallery in Otegem.

The way Van Schuylenbergh picked up on this new pictorial style caught the attention of a number of critics and gallery owners, but he never availed himself of their interest. Their appreciation was understandable, as Van Schuylenbergh had immediately found hisown voice within the movement. The pop art he made at that time is now, fifty years later, for the very first time on display at the DISKUS exhibition space (Aalst, December 2022). Nicely attired in their anti-conformist 1970s outfits, his family members, friends and esteemed colleagues have been immortalised posing in a cheerful decor. A self-portrait has of course been included. His subjects' positive attitude to life is in stark contrast to the existential miserabilism connected with Sartre's philosophicalstance. The world can also be beautiful, is what André Van Schuylenbergh, the painter of optimism, isshowing us.

And he is right, if only in times of carnival.

Reactie plaatsen

Reacties